Parasites in the blood supply, and 7 other things you need to know about Babesia 04/27/2012

Posted by thetickthatbitme in TBI Facts.Tags: Babesia, Blood donation, Blood transfusion, health, Malaria, medicine, Mepron, parasite, pregnancy, Rhode Island Blood Center, tick bite

6 comments

The fact sheet for Babesia is up today. Here are a few (disturbing) highlights:

1. Babesia is a parasite that attacks red blood cells. There are three ways Babesia spreads: 1) Through the bite of the blacklegged tick (or deer tick, Ixodes scapularis—the same tick that carries Lyme/B. burgdorferi); 2) Through blood transfusions with contaminated donated blood; 3) From mother to baby during pregnancy or childbirth.

A nymphal stage Ixodes scapularis tick (approximately the size of a poppy seed) is shown here on the back of a penny. Credit: G. Hickling, University of Tennessee.

2. The tick that carries Babesia is most likely to infect humans when it’s in its nymphal stage. During this stage, the tick is about the size of a poppy seed. (Maybe this is one reason why Babesia cases are on the rise among older people–they probably have trouble spotting ticks that small!)

3. Many people who have a Babesia infection don’t show any symptoms. When they do show symptoms, they can include fever, chills, sweats, headache, body aches, loss of appetite, nausea, and fatigue. Some develop hemolytic anemia, which causes jaundice and dark urine.

4. Babesia can be deadly if it goes untreated. Here are some possible complications: low and unstable blood pressure; altered mental status; severe hemolytic anemia (hemolysis); very low platelet count (thrombocytopenia); disseminated intravascular coagulation (also known as “DIC” or consumptive coagulopathy), which can lead to blood clots and bleeding; and malfunction of vital organs (such as the kidneys, liver, lungs, and heart).

5. There are two main treatment options for Babesia: a combination of Mepron and Zithromax OR a combination of Clindamycin and Quinine. Children and women who are pregnant should probably not be treated with Mepron.To read more about treatment, go to the Babesia fact sheet.

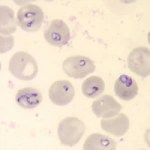

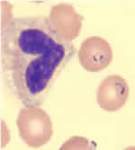

6. Babesia is sometimes confused with Malaria because they look similar under a microscope and can have similar symptoms. To avoid confusion, doctors should order multiple types of tests for Babesia if patients show symptoms. To read more about available tests, see the fact sheet.

- Babesia parasites in red blood cells on a stained blood smear. (CDC Photo: DPDx). Via CDC.gov.

- Blood smear stained with Giemsa, showing a white blood cell (on left side) and several red blood cells, two of which are infected with Plasmodium falciparum (Malaria) (on right side). Image via CDC.gov.

7. There are 4 identified species of Babesia that infect humans: Babesia microti, B. divergens, B. duncani (WA-1), and MO-1 (unnamed strain). Antibody tests for Babesia are species specific, so if you have B. microti and you are tested for B. duncani, the test will come back negative. This means that patients need to undergo multiple blood tests!

8. Even though Babesia infection is known to be transmitted through blood transfusion (As of Sept. 2011, the CDC has identified 159 cases, and at least 12 of those people have died.), donated blood is not tested for Babesia! Donors are asked to fill out a questionnaire asking whether they have Babesia (not whether they’ve had tick bites or Babesia-like symptoms). In other words, we are relying on patient self-reporting to screen the blood supply for this parasite! (Why they don’t screen out all people who’ve had tick bites is beyond me.) The CDC’s response as to whether they will implement testing of donated blood for Babesia in the future: Maybe. They say they are going to “Monitor reports of tick-borne infection to determine if the disease is spreading to other parts of the country and to identify emerging strains of Babesia that may cause human disease.” In other words, they’re going to wait to see how bad it gets before they do anything about the blood supply. Some organizations like the Rhode Island Blood Center have begun screening blood for Babesia using an experimental test, but this is not mandated by CDC policy.

This might prompt you to ask: What are my local health department, hospitals, and blood donation organizations doing about Babesia in the blood supply?

Have questions or something to add about Babesia? Drop me a comment.

Related articles

- Well, Babs, you’re trickier than I thought (thetickthatbitme.com)

Eight things you need to know about Anaplasmosis 04/25/2012

Posted by thetickthatbitme in Diagnosis, TBI Facts.Tags: Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Anaplasmosis, Borrelia burgdorferi, doxycycline, health, labs, Lyme Disease, medicine, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, tick, treatment

5 comments

A new fact sheet is up today for Anaplasmosis, otherwise known as Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection. Try saying that three times fast. This is one of the two TBIDs I’ve been unlucky enough to have, but I had never heard of it before my lab results came back with a positive antibody test for it. By the end of this post, you’ll know eight things you didn’t know before about Anaplasmosis.

A microcolony of A. phagocytophylum visible in a granulocyte (white blood cell) on a peripheral blood smear. Image via CDC.gov.

1. Anaplasmosis is spread by the same ticks that spread Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme Disease). This means that people with Lyme can have a coinfection with Anaplasmosis (and some of them don’t know it).

2. The symptoms of an Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection are: fever, headache, muscle pain, malaise, chills, nausea / abdominal pain, cough, and confusion. Some people get all the symptoms; other people only get a few.

3. If you show symptoms of Anaplasmosis, your doctor shouldn’t wait for lab results to come back to begin treating you. The CDC recommends beginning treatment right away.

4. If you’ve been infected with Anaplasma phagocytophilum and you get tested within the first 7-10 days you are sick, the test might come back negative. This doesn’t mean you don’t have Anaplasmosis, and you’ll need to be tested again later.

5. The best way to treat Anaplasmosis is with the antibiotic Doxycycline. According to the CDC, other antibiotics should not be substituted because they increase the risk of fatality. If your doctor insists on treating your Anaplasmosis with something other than Doxycycline, it’s probably time to get a new doctor. For people with severe allergies to Doxycycline or for women who are pregnant, the drug Rifampin can be used to treat Anaplasmosis.

6. Anaplasmosis can be confused with other TBIDs in the rickettsia family like Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) and ehrlichiosis. These infections are also commonly treated with Doxycycline.

7. The number of cases of Anaplasmosis reported to the CDC has increased steadily since 1996. You can attribute this to climate change or not, but the trend suggests that this disease will be an increasingly more common problem in the future.

8. More than half of Anaplasmosis cases are reported in the spring and summer months. This is a no-brainer, since this is when tick populations thrive. To avoid infection, take steps to avoid tick exposure for both you and your pets.

What Is Prophylaxis, and Does It Work on Tick Bites? 04/24/2012

Posted by thetickthatbitme in Peer-Reviewed, Tick-Lit, Treatment.Tags: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia hermsii, Borrelia persica, CDC, doxycycline, health, Israel, Lyme Disease, medicine, NEJM, prevention, prophylaxis, research, TBRF, tick bite, treatment

3 comments

Today is Tuesday, and I’ve made an executive decision that from now on, every Tuesday I will be covering peer-reviewed research related to tick-borne infections. We in academia call this a “review of the literature,” even though it’s not what normal people think of as literature–no Shakespeare, just dry prose littered with scientific jargon–which is why most people don’t want to read it. Lucky for you, I am a super-nerd and enjoy this kind of reading, at least when it’s about TBIDs (tick-borne infectious diseases). I’ve even come up with an affectionate name for it: “tick-lit”. So every Tuesday from here on out will be Tick-Lit Tuesday, the day on which I read the literature so you don’t have to. Enjoy!

Today’s question: Does prophylaxis work for tick bites?

While a lot of patients with tick-borne infections don’t remember a tick or a tick bite (which is why it takes so long to get diagnosed), there are also people who do notice being bitten and go to a doctor right away because they are concerned about TBIDs. So what happens to these patients?

I’ve heard stories from patients with TBIDs, particularly patients with Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme) and Borrelia hermsii (Tick-borne Relapsing Fever), about how when they went to a doctor within 48 hours of being bitten, they were told “Oh, we don’t have Lyme in this state, so you don’t have to worry.” Following this logic, ticks carrying Borrelia burgdorferi must be so smart that 1) they know which bacteria they are carrying; 2) they know which state they are in; and 3) they have the decency to respect state lines. I can really imagine a deer tick saying, “Oh, no, I can’t go over there. I’m a California tick. They don’t let dirty ticks like me out of California.” I suppose some doctors imagine that there is some kind of tick parole system that keeps them from traveling anywhere where the CDC and state health departments have not documented them to exist.

Some of these delusional doctors probably can’t be reasoned with, but what about doctors who want to do the right thing? What should they do when a patient comes to them within 48 hours of a tick bite?

Let’s take a look at the research.

One of my favorite tick-lit studies is one that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine way back in July 2006. The study took place in Israel, where Ornithodoros tholozani ticks infect people with a bacterium called Borrelia persica. Borrelia persica, like Borrelia hermsii, causes Tick Borne Relapsing Fever (TBRF). You can think of Borrelia persica as B. hermsii‘s brother. The researchers wanted to find out whether prophylaxing soldiers (giving them antibiotics right away) who had recently been bitten by ticks would prevent the infection from spreading and causing the symptoms of TBRF.

Here’s how they did it (Methods). They studied 93 healthy soldiers with suspected tick bites. Some of these people had evidence of a tick bite (like a rash) and others didn’t, but had been in the same places that the people with bites had, so they had the same risk of exposure. They randomly picked half of the soldiers who would receive antibiotics (Doxycycline for 5 days), and the other half would receive a placebo (which means they would think that they were taking antibiotics, but they were really taking a sugar pill). The study was double-blind, which means that neither the soldiers nor the researchers knew which patients were given the real antibiotics at the time of the study. This makes the study more credible.

Here’s what happened (Results):

All 10 cases of TBRF identified by a positive blood smear were in the placebo group of subjects with signs of a tick bite (P<0.001). These findings suggested a 100 percent efficacy of preemptive treatment (95 percent confidence interval, 46 to 100 percent). PCR for the borrelia glpQ gene was negative at baseline for all subjects and subsequently positive in all subjects with fever and a positive blood smear. Seroconversion was detected in eight of nine cases of TBRF. PCR and serum samples were negative for all of the other subjects tested. No major treatment-associated adverse effects were identified.

In English, this means that 10 of the 46 people who did not get treated with antibiotics got sick with TBRF, and their blood tests showed that they were making antibodies to Borrelia persica. (Their PCR test (a DNA test) was also positive for the borrelia gene.) However, none of the 47 people who were treated with antibiotics developed any symptoms of TBRF. When their blood was tested, it was negative for antibodies to Borrelia persica and their PCR was negative for the borrelia gene. That means that prophylaxing with Doxycycline prevented 100% of cases of TBRF (Borrelia perica infection).

- Doxycycline Structure. Image via Wikipedia.

- Doxycycline 3D structure. Image via Wikipedia.

Now you may say to yourself, “Oh, that’s only one study. The sample size was fairly small, and it’s not necessarily generalizable to all Borrelia infections.” At least, that’s what I imagined you (or your skeptical primary doctor) saying as I was rooting around on PubMed. Then I dug up this study from *gasp* 2001: “Prophylaxis with single-dose doxycycline for the prevention of Lyme disease after an Ixodes scapularis tick bite” (!!!)

The 2001 study was conducted in an area of New York with a high incidence of Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme) infection. Like the Israeli study, it was also a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, but unlike the Israeli study, they only gave patients a single dose of doxycycline. The results? One out of the 235 people treated with doxycycline got Erythema migrans, the bull’s-eye rash that indicates a Borrelia burgdorferi infection. In the placebo group (people who didn’t get antibiotics) 8 out of 235 developed the rash and tested positive for infection. Their conclusion: a single dose of doxycycline can prevent Lyme if given within 72 hours of the tick bite.

If these two studies are not convincing or current enough, the doctors from the Israeli Medical Corps published another study in 2010. First, they inform us that “Since 2004, the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) has mandated the prophylaxis of tick-bitten subjects with a five-day doxycycline course.” (That has me thinking the Israelis are pretty smart.) Just to make sure they were doing the right thing, in this study, they decided to analyze all the tick bite and TBRF cases in their records from 2004-2007.

Here’s what they say:

Of those screened, 128 (15.7%) had tick-bite and were intended for prophylaxis, of which four TBRF cases occurred-3.13% attack rate compared with an expected rate of 38.4% in these bitten individuals without prophylaxis (RR = 0.08, number needed to treat = 3). In all cases in which screening and prophylaxis were provided within 48 h of tick bite, complete prevention of TBRF was achieved. No cases of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (JHR) was recorded.

What does that mean? Only 4 of the 128 people who were treated with doxycycline developed TBRF, a rate of 3.13%. The expected attack rate was more than 10 times that, 38 percent, so without the doxycycline policy, it would likely have been 48 people with TBRF instead of 4. One more thing. There was a reason those four people got sick: they were given the doxycycline later than 48 hours after being bitten!

The Big Picture

How does this research affect you as a patient who has been bitten by a tick and contracted an infection or as a patient who could potentially be bitten by a tick in the future?

The research shows us that, if treated within 48 hours with 5 days of Doxycycline, most–if not all–cases of Borrelia infection and resulting symptoms can be prevented. If you could get an appointment with an infectious disease specialist who recognizes this fact within 48 hours of being bitten, you could probably avoid a lot of potential suffering. The problem is that to see a specialist, you usually need to be referred by your primary care doctor. Some of us can’t even get an appointment to see our primary care doctors within 48 hours, and some of the primary care doctors don’t even know how to spell Borrelia (no offense to primary care doctors who can spell it), let alone diagnose it with a simple blood test. And most of them certainly don’t know that the best thing to do would be to prophylax you with doxycycline.

Let’s put the numbers in perspective. In 2010, the CDC reported over 20,000 confirmed cases of Lyme (Borrelia burgdorferi) and an additional 10,000 probable cases. The CDC’s number of cases (which I believe, as with burgdorferi, are severely underreported) for 1990-2011 for Borrelia hermsii (TBRF) is 483. If 35% of those Borrelia cases had been prevented with prophylaxis, that would mean 10,669 fewer sick people.

So what can you do? Here’s a list of my suggestions:

- If you’ve been diagnosed with a tick-borne illness, make sure that every one of your doctors knows it, even the ones you don’t like and the ones you don’t go to very often. All doctors, not just infectious disease doctors, need to be aware of how prevalent these infections are.

- If you are bitten by a tick, insist that your primary care doctor prophylax you with doxycycline for five days. You can even print out these PubMed article abstracts and bring them to your appointment. Many doctors can be reasoned with, and if they won’t listen to you, sometimes they’ll listen to the New England Journal of Medicine.

- If you are bitten by a tick, try your best to save the little beast. You can store it in an old prescription bottle or a jar. (Labs like Quest Diagnostics also distribute collection containers to some doctors’ offices.) Inform your doctor that you are brining the tick to your appointment and you want to have it tested. Having ticks tested helps with more accurate CDC reporting about which areas have infected ticks.

- Getting the tick tested doesn’t mean that you don’t need to get tested. The tick testing takes longer than the people testing. On the off-chance that prophylaxis doesn’t work for you, you’ll need to get more treatment if you test positive.

- As always, the best way not to get a tick bite is not to be in areas where ticks live and not to be around animals that carry ticks. Follow tick-exposure prevention best practices. This includes keeping your home and yard free of mice and rats (on which the hermsii-carrying ticks feed) as well as deer (on which the burgdorferi-carying ticks feed).

That’s all for Tick-Lit Tuesday. Stay informed and stay well!