Well, Babs, you’re trickier than I thought 05/01/2012

Posted by thetickthatbitme in Diagnosis, Peer-Reviewed, TBI Facts, Tick-Lit.Tags: Babesia, Blood donation, Blood transfusion, health, IFA, labs, Lyme, medicine, PCR, smear, tick

1 comment so far

Welcome to the second installment of Tick-Lit Tuesday, where I comb through PubMed so you don’t have to. Today’s topic: Babesia and Blood Transfusions. Now, I know I posted about Babesia in the blood supply just a few days ago, but an interesting study has since come to my attention (thanks, Dr. W), and the implications are a bit scary. Okay, get your popcorn and let’s begin.

The Issue:

It has been well-documented that the tick-borne protozoan parasite Babesia can be contracted through blood transfusions. Blood centers aren’t required to test donated blood for Babesia, but this may change in the future, as Babesia infections contracted through transfusions are on the rise. So if we were to test all donors for Babesia prior to donation, which tests should we rely on to detect this pesky parasite? Let’s look at the candidates.

IFA: IFA is an abbreviation for indirect fluorescent antibody test. This type of test can also be referred to as serologic (as in blood serum) testing. If you’ve had one of these tests for Babesia, it’s probably titled something like “WA1 IGG ANTIBODY IFA” (for B. duncani) or “BABESIA MICROTI ABS IGG/IGM” on your lab results. If you’ve had Babesia in the past and been treated for it, your antibody test might still read positive because your body is still making antibodies to the parasite. This is one of the reasons why most insurance companies refuse to pay for treatment for Babesia if your only positive test is the IFA. They think maybe you had a past infection that you got over, so you don’t need treatment. (The other reason they refuse to pay is that they’re jerks, to put it nicely.) I’ll talk more about why this is such a problem later in this post.

A stained blood smear on which B. microti parasites are visible in red blood cells. (CDC Photo: DPDx). Via CDC.gov.

Smear: When we talk about a smear for Babesia, we mean a Giemsa-stained thin blood smear. This test involves looking at blood samples under a microscope to see if there are any parasites hanging around. The problem with this test is that Babesia can infect fewer than 1% of your circulating red blood cells, so it could take many, many smears before any Babesia show up under the microscope. For more information about that phenomenon, read this.

PCR: This stands for polymerase chain reaction. It’s basically a DNA test that tries to identify whether a gene associated with Babesia is present in the blood. PCR has been found to be “as sensitive and specific” as blood smears for Babesia (see this study), which is not saying much, considering the tendency of Babesia to go undetected with smears.

Hmmm, for whom shall I cast my ballot, the antibody test insurance companies don’t trust, the inaccurate smear, or the inaccurate PCR? Choices, choices…

Today’s question:

Can the donated blood of someone with a negative PCR and negative blood smear still be infected with Babesia and cause Babesia infection in transfusion recipients?

(Hint: This is a leading question.)

Let’s talk about a study published in the journal Transfusion in December of 2011 called “The third described case of transfusion-transmitted Babesia duncani.”

Here’s what happened:

In May 2008, a 59 year-old California resident (I’ll call him Cal) with sickle-cell disease had some red blood cell transfusions. Cal’s only risk factor for Babesia was the transfusions; he didn’t have any tick exposure. In September of 2008, Cal was diagnosed with a Babesia duncani (WA-1) infection. The parasites were visible on a blood smear, the indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test was positive, and the PCR was positive for the Babesia gene. This launched a transfusion investigation in which doctors tracked down 34 of the 38 blood donors whose blood could have infected Cal with Babesia. One donor, a 67-year-old California resident (who I’ll call Don) had a B. duncani titer of 1:4096 (on the IFA test). What does a titer of 1:4096 mean? Well, if the antibody test for B. duncani is negative, the titer will be < 1:256. That means that Don’s antibody test was positive.

What the article abstract doesn’t tell you, which the full article does, is that both Don’s PCR and blood smear were negative for Babesia. How did the researchers prove definitively that Don had Babesia in his blood? They injected the blood into Mongolian gerbils, and were later able to isolate the parasite from the gerbils. Conclusion: Even though Don showed no symptoms of Babesia and both his PCR and smear were negative, his donated blood caused Babesiosis in both Cal and the gerbils.

Here’s why the study’s findings are important:

1. Clearly, blood smears and PCRs are not good indicators of whether someone is infected with Babesia. Why insurance companies think these tests need to be positive before they’ll pay for treatment is a mystery to me. There are probably a lot of people out there who’ve had positive IFAs but negative smear and/or PCR who were then not treated for Babesia because either the doctor, the insurance company, or both said they didn’t have an infection.

2. As far as the blood donation goes, if we don’t start screening out donors with positive Babesia IFAs, we’re going to continue to contaminate the blood supply with Babesia. It should be as simple as that. Been bitten by a tick? No blood donation for you. Positive IFA? No blood donation for you.

DZWSQK6QYS9G

Related articles

Eight things you need to know about Anaplasmosis 04/25/2012

Posted by thetickthatbitme in Diagnosis, TBI Facts.Tags: Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Anaplasmosis, Borrelia burgdorferi, doxycycline, health, labs, Lyme Disease, medicine, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, tick, treatment

5 comments

A new fact sheet is up today for Anaplasmosis, otherwise known as Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection. Try saying that three times fast. This is one of the two TBIDs I’ve been unlucky enough to have, but I had never heard of it before my lab results came back with a positive antibody test for it. By the end of this post, you’ll know eight things you didn’t know before about Anaplasmosis.

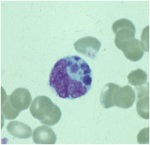

A microcolony of A. phagocytophylum visible in a granulocyte (white blood cell) on a peripheral blood smear. Image via CDC.gov.

1. Anaplasmosis is spread by the same ticks that spread Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme Disease). This means that people with Lyme can have a coinfection with Anaplasmosis (and some of them don’t know it).

2. The symptoms of an Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection are: fever, headache, muscle pain, malaise, chills, nausea / abdominal pain, cough, and confusion. Some people get all the symptoms; other people only get a few.

3. If you show symptoms of Anaplasmosis, your doctor shouldn’t wait for lab results to come back to begin treating you. The CDC recommends beginning treatment right away.

4. If you’ve been infected with Anaplasma phagocytophilum and you get tested within the first 7-10 days you are sick, the test might come back negative. This doesn’t mean you don’t have Anaplasmosis, and you’ll need to be tested again later.

5. The best way to treat Anaplasmosis is with the antibiotic Doxycycline. According to the CDC, other antibiotics should not be substituted because they increase the risk of fatality. If your doctor insists on treating your Anaplasmosis with something other than Doxycycline, it’s probably time to get a new doctor. For people with severe allergies to Doxycycline or for women who are pregnant, the drug Rifampin can be used to treat Anaplasmosis.

6. Anaplasmosis can be confused with other TBIDs in the rickettsia family like Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) and ehrlichiosis. These infections are also commonly treated with Doxycycline.

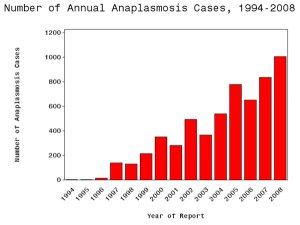

7. The number of cases of Anaplasmosis reported to the CDC has increased steadily since 1996. You can attribute this to climate change or not, but the trend suggests that this disease will be an increasingly more common problem in the future.

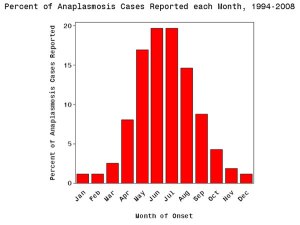

8. More than half of Anaplasmosis cases are reported in the spring and summer months. This is a no-brainer, since this is when tick populations thrive. To avoid infection, take steps to avoid tick exposure for both you and your pets.