9 things you need to know about Borrelia miyamotoi 02/18/2013

Posted by thetickthatbitme in Diagnosis, Media, TBID Facts.Tags: Borrelia, Borrelia hermsii, Borrelia miyamotoi, health, Lyme Disease, medicine, New England Journal of Medicine, Relapsing Fever, tick bite, tick-borne relapsing fever

4 comments

Several months ago, when the patient support group that I attend first began discussing Borrelia miyamotoi, a Google search (or Bing…whatever…) for those two odd words yeilded very little. Now, after the publishing of a few key papers in the New England Journal of Medicine, every major news outlet seems to be aware of this “new” Borrelia.

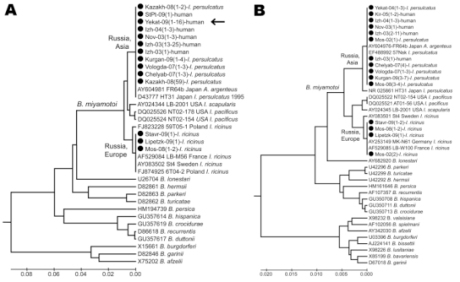

From a scientific perspective, Borrelia miyamotoi is interesting because it challenges a dichotomy that was established by researchers of tick-borne infectious diseases. When I first started reading about the Borrelia genus, I learned that Borrelia species could be sorted into two major categories: the Lyme disease-like group and the relapsing fever group. That is, Borrelia species like B. burgdorferi, B. afzelli, and B. garinii–which are genetically more similar, are carried by hard-bodied ticks, and cause the same pattern of symptoms (rash, joint pain, fatigue–were put in one group. Other species, like B. hermsii and B. parkeri–which differ genetically from these Lyme-like bacteria, are carried by soft-bodied ticks, and all cause relapsing fever symptoms–were put in the other group. One group for Lyme-like illness. Another group for relapsing fever-like illness. One group for hard-bodied ticks. Another group for soft-bodied ticks. The dichotomy is so clear that the ticks are sometimes referred to as “Lyme disease ticks” and “relapsing fever ticks.”

The funny thing about dichotomies is that they only create the illusion of two distinct categories. The reality is far more messy and characterized by shades of grey. Enter Borrelia miyamotoi. According to its genetics, it should go in the relapsing fever group, but it’s transmitted by the same hard-bodied ticks that carry Lyme disease. According to its symptoms, it falls somewhere in the middle. About 10% of people get a rash, like with Lyme disease, while others don’t. Some people get relapsing fevers, while others don’t. It’s all so very confusing!

A Borrelia family tree (technically called a phylogenetic tree) highlighting strains of B. miyamotoi. Note the groupings of the other Borrelia. Via Platonov AE, Karan LS, Kolyasnikova NM, Makhneva NA, Toporkova MG, et al. (2011) Humans infected with relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi, Russia. Emerg Infect Dis 17: 1816–1823.

As usual, both the researchers and the news media seem to be trying to downplay this. Some are unwittingly obscuring the issue altogether. “Paging Dr. House: There [sic] a new tick-transmitted spirochete in town…” writes Melissa Healey of the L.A. Times. “The New England Journal of Medicine on Thursday published two reports documenting its arrival on U.S. shores.” As if the bacteria hopped on a boat from Russia, and that’s how it got here! Forget the strong possibility that it was here all along and our scientists just failed to detect it. Forget the possibility that the countless numbers of people who tested negative for Lyme disease and were denied treatment could in fact have this similar infection.

Dr. Peter Krause, lead author on the NEJM study, says (in a video for Yale News) he doesn’t think people should panic about Borrelia miyamotoi. At the same time, he admits that this is an infection that is affecting people in both the eastern and western United States–not to mention people in Europe and Asia. “We expect this disease to be found everywhere the deer tick is found,” he states. So don’t panic, but it’s everywhere.

Okay, so Dr. Krause is right when he says people shouldn’t panic, but that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t learn more about this new–or not so new, as the case may be–infection, especially since many of us could have it right now. Here are nine things I think you should know about Borrelia miyamotoi.

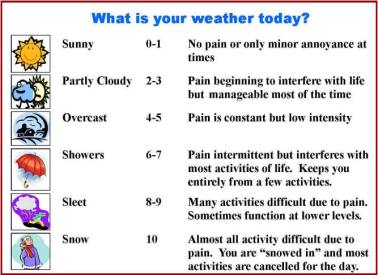

1. Symptoms: Borrelia miyamotoi causes symptoms of tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF), an illness often misdiagnosed as Lyme disease, or not diagnosed at all. Tick-borne relapsing fever, when left untreated, has some symptom overlap with Lyme: arthralgias, myalgias, chronic fatigue, and cognitive problems; however, it differs from Lyme disease in that most patients with TBRF get repeated episodes of fever, and they don’t get erythema chronicum migrans (EM), the “classic Lyme” bull’s-eye rash. We can guess that the long-term effects of B. miyamotoi infection are similar to those of other Borrelia infections, even if researchers are reluctant to admit it. Dr. Peter Krause, one of the authors of the study published in the January 17 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, told the L.A. Times: “This is a very new disease, but none of the patients have had this long-term [neurological] trouble or other long-term symptoms,[…] it’s possible that we just haven’t seen it yet.” Long-term neurological problems from a disease that most doctors didn’t know existed until a few months ago? I’d say it’s very possible.

2. Transmission: Borrelia miyamotoi is transmitted to humans from the bites of hard-bodied ticks. Examples of these ticks include Ixodes scapularis (deer tick), Ixodes pacificus (western blacklegged tick), Ixodes ricinus (castor bean tick), and Ixodes persulcatus (taiga tick). (The first two tick species listed are common in North America, and the second two are found in Europe and Asia.)

3. Why you’re just hearing about it now: The B. miyamotoi bacterium was discovered in ticks and mice in Japan back in 1995. (It’s named after Japanese entomologist Kenji Miyamoto, who first isolated the bacterium.) In 2001, Dr. Durland Fish discovered B. miyamotoi in ticks in Connecticut, but according to a 2011 New York Times report, he “was repeatedly refused a study grant [from NIH] until the Russians proved it caused illness.” In 2011, Russian scientists, in collaboration with the Yale team that included Krause and Fish, published research that showed that B. miyamotoi infects humans. The patients in the 2011 study were in Russia, so B. miyamotoi didn’t really come on the radar for U.S. doctors until January 2013, when a study on U.S. patients was published by Krause and colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine.

4. Testing: To my knowledge, there is currently no commercially-available test for B. miyamotoi, be it PCR, IFA, or Western Blot. B. miyamotoi has been detected using assays (tests) that were developed by university researchers in order to study the bacterium. That means, unless your doctor is at Yale or another large institution, it’s not likely that he or she has access to a test for B. miyamotoi. So if you suspect you may be infected, what can you do? That brings me to my next point.

5. People with B. miyamotoi infection are likely to test negative for B. burgdorferi (Lyme disease), unless they also happen to be infected with B. burgdorferi. Doctors who are only screening patients for Lyme disease are not going to catch all of the other Borrelia infections, like B. miyamotoi.

6. Genetically, B. miyamotoi is more similar to other bacteria that cause TBRF, like Borrelia hermsii. Therefore, people with B. miyamotoi infection may test positive for B. hermsii, another relapsing fever spirochete.

7. As with any infection, B. miyamotoi infection can be more serious in the elderly and in patients with compromised immune systems. If you or a family member is denied treatment, especially in the case of severe or life-threatening symptoms (like high fever), my advice would be to go to a tertiary care center (like a university hospital) and ask to be tested for B. miyamotoi. At the very least, doctors at a research hospital should be able to do a blood smear to look for spirochetes (Borrelia). PCR and antibody tests may also be available.

8.Treatment: B. miyamotoi probably responds in a similar way to antibiotics as other Borrelia like B. hermsii and B. burgdorferi. Researchers claim that it can be treated with a few weeks of oral antibiotics, but that is probably only for mild, acute cases. My guess (as a non-medical-professional) is that B. miyamotoi is just as resilient as its Borrelia cousins and requires 4-6 weeks of daily IV antibiotics. If you’re new to this blog, you might be interested in reading about my experience being treated with IV antibiotics for B. hermsii (relapsing fever).

9. Recommended reading: To learn more about B. miyamotoi, check out the new fact sheet, which includes links to peer-reviewed studies.

Related articles

The Choline Diet: Herbivore Style 07/01/2012

Posted by thetickthatbitme in Choline Diet, Tick-Lit, Whole Person.Tags: allergy, Anaplasmosis, Borrelia, Borrelia hermsii, choline, diet, health, Lyme Disease, meat, steak, vegetarian

add a comment

In the past, my choline diet posts have been mostly geared towards omnivores, as eating eggs and meat is an easy way to get one’s daily dose of choline. If you’re new to this blog–or just forgetful–I’ve been on a choline-rich diet since I started getting treated for Borrelia hermsii and Anaplasmosis last year. My doctor recommended this because I had some neurological involvement with my illness–brain fog, chronic fatigue, arthralgias–and there’s research that suggests that eating choline helps our bodies produce more of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Choline has also been linked to lower levels of inflammation. In addition, choline is particularly important for pregnant women, as higher choline intake during pregnancy is associated with a lower risk of neural tube defects in infants.

So that’s why I’m always telling my readers to eat their eggs and meat and green veggies. However, since a study led by Scott Commins at the University of Virginia linking lone star tick bites to red meat allergies gained national media attention (ABC, CNN) a few weeks ago, I’ve been thinking about how to make my choline recipe recommendations more herbivore-friendly.

After my last choline-related post, I stumbled upon the USDA Database for the Choline Content of Common Foods, which is a fairly good resource (and handy since it comes in a searchable PDF), although it doesn’t include everything I like to eat. (For example, the desserts section is severely lacking.) The other issue with it is that the choline values are reported in mg per 100 grams of food, and the average person may not eat 100 grams of some of those food items in one sitting–particularly the spices. (100 grams of chili powder, anyone?) So keep in mind that the choline numbers below are based on that ratio, and don’t think you’re getting 120 mg of choline in a pinch of mustard seed. This week, I decided to go through the database and find the foods with the most choline. For my herbivore/vegetarian readers out there, whatever your reason for avoiding meat (moral, dietary, tick-bite-induced allergy…), here are the top choline sources from several non-meat categories:

Top 10 Veggies:

- edamame—56 mg*

- broccoli (boiled) —40 mg

- cauliflower (boiled) —39 mg

- tomato paste—39 mg

- artichokes (boiled)—34 mg

- peas (boiled)—28 mg

- spinach (cooked) —28 mg

- asparagus (boiled) —28 mg

- sweet corn (boiled) —22 mg

- red potatoes (baked) —19 mg

Top 10 Fruits:

- dried figs—16 mg

- clementines—14 mg

- avocados—14 mg

- dried apricots—14 mg

- raspberries—12 mg

- raisins—11 mg

- prunes—10 mg

- mandarin oranges—10 mg

- medjool dates—9.9 mg

- bananas—9.8 mg

Top 10 Nuts and Seeds:

- flaxseed—79 mg

- dry roasted pistachios—71 mg

- roasted pumpkin seed kernels—63 mg

- roasted cashews—61 mg

- dried pine nuts—56 mg

- sunflower seed kernels—55 mg

- almonds—52 mg

- hazelnuts—46 mg

- dry roasted macadamia nuts—45 mg

- pecans—41 mg

Top 5 Legumes:

- creamy peanutbutter—66 mg

- boiled navy beans—45 mg

- baked beans—28 mg

- firm tofu—28 mg

- soft tofu—27 mg

Top 10 Spices:

- mustard seed—120 mg

- dried parsley—97 mg

- garlic powder—68 mg

- chili powder—67 mg

- curry powder—64 mg

- dried basil—55 mg

- paprika—52 mg

- ground turmeric—49 mg

- ground ginger—41 mg

- onion powder—39 mg

*All measurements are given in mg/100 g of food

I hope these lists get you on your way to a diet more rich in choline, whether it includes meat or not.

This concludes the herbivore section of this post. If you don’t want to be tempted with any meat, try clicking over to some of my other posts.

***

If you’re here in search of choline diet inspiration of the omnivore variety, I haven’t completely forgotten you. Here’s a glimpse of what I had for lunch.

Happy Sunday, everybody! And watch out for ticks!

Related articles

- Eat Your Eggs, Benedict!

- Snacking in the name of choline

- Ehrlichia: confusing cousins, the blood supply, and the new kid on the block

- My Story

- Four (surprising) places ticks hang out

- Fresh Friday: 10 Reasons to Eat Egg Yolks (doubleeaglefitness.wordpress.com)

What Is Prophylaxis, and Does It Work on Tick Bites? 04/24/2012

Posted by thetickthatbitme in Peer-Reviewed, Tick-Lit, Treatment.Tags: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia hermsii, Borrelia persica, CDC, doxycycline, health, Israel, Lyme Disease, medicine, NEJM, prevention, prophylaxis, research, TBRF, tick bite, treatment

3 comments

Today is Tuesday, and I’ve made an executive decision that from now on, every Tuesday I will be covering peer-reviewed research related to tick-borne infections. We in academia call this a “review of the literature,” even though it’s not what normal people think of as literature–no Shakespeare, just dry prose littered with scientific jargon–which is why most people don’t want to read it. Lucky for you, I am a super-nerd and enjoy this kind of reading, at least when it’s about TBIDs (tick-borne infectious diseases). I’ve even come up with an affectionate name for it: “tick-lit”. So every Tuesday from here on out will be Tick-Lit Tuesday, the day on which I read the literature so you don’t have to. Enjoy!

Today’s question: Does prophylaxis work for tick bites?

While a lot of patients with tick-borne infections don’t remember a tick or a tick bite (which is why it takes so long to get diagnosed), there are also people who do notice being bitten and go to a doctor right away because they are concerned about TBIDs. So what happens to these patients?

I’ve heard stories from patients with TBIDs, particularly patients with Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme) and Borrelia hermsii (Tick-borne Relapsing Fever), about how when they went to a doctor within 48 hours of being bitten, they were told “Oh, we don’t have Lyme in this state, so you don’t have to worry.” Following this logic, ticks carrying Borrelia burgdorferi must be so smart that 1) they know which bacteria they are carrying; 2) they know which state they are in; and 3) they have the decency to respect state lines. I can really imagine a deer tick saying, “Oh, no, I can’t go over there. I’m a California tick. They don’t let dirty ticks like me out of California.” I suppose some doctors imagine that there is some kind of tick parole system that keeps them from traveling anywhere where the CDC and state health departments have not documented them to exist.

Some of these delusional doctors probably can’t be reasoned with, but what about doctors who want to do the right thing? What should they do when a patient comes to them within 48 hours of a tick bite?

Let’s take a look at the research.

One of my favorite tick-lit studies is one that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine way back in July 2006. The study took place in Israel, where Ornithodoros tholozani ticks infect people with a bacterium called Borrelia persica. Borrelia persica, like Borrelia hermsii, causes Tick Borne Relapsing Fever (TBRF). You can think of Borrelia persica as B. hermsii‘s brother. The researchers wanted to find out whether prophylaxing soldiers (giving them antibiotics right away) who had recently been bitten by ticks would prevent the infection from spreading and causing the symptoms of TBRF.

Here’s how they did it (Methods). They studied 93 healthy soldiers with suspected tick bites. Some of these people had evidence of a tick bite (like a rash) and others didn’t, but had been in the same places that the people with bites had, so they had the same risk of exposure. They randomly picked half of the soldiers who would receive antibiotics (Doxycycline for 5 days), and the other half would receive a placebo (which means they would think that they were taking antibiotics, but they were really taking a sugar pill). The study was double-blind, which means that neither the soldiers nor the researchers knew which patients were given the real antibiotics at the time of the study. This makes the study more credible.

Here’s what happened (Results):

All 10 cases of TBRF identified by a positive blood smear were in the placebo group of subjects with signs of a tick bite (P<0.001). These findings suggested a 100 percent efficacy of preemptive treatment (95 percent confidence interval, 46 to 100 percent). PCR for the borrelia glpQ gene was negative at baseline for all subjects and subsequently positive in all subjects with fever and a positive blood smear. Seroconversion was detected in eight of nine cases of TBRF. PCR and serum samples were negative for all of the other subjects tested. No major treatment-associated adverse effects were identified.

In English, this means that 10 of the 46 people who did not get treated with antibiotics got sick with TBRF, and their blood tests showed that they were making antibodies to Borrelia persica. (Their PCR test (a DNA test) was also positive for the borrelia gene.) However, none of the 47 people who were treated with antibiotics developed any symptoms of TBRF. When their blood was tested, it was negative for antibodies to Borrelia persica and their PCR was negative for the borrelia gene. That means that prophylaxing with Doxycycline prevented 100% of cases of TBRF (Borrelia perica infection).

- Doxycycline Structure. Image via Wikipedia.

- Doxycycline 3D structure. Image via Wikipedia.

Now you may say to yourself, “Oh, that’s only one study. The sample size was fairly small, and it’s not necessarily generalizable to all Borrelia infections.” At least, that’s what I imagined you (or your skeptical primary doctor) saying as I was rooting around on PubMed. Then I dug up this study from *gasp* 2001: “Prophylaxis with single-dose doxycycline for the prevention of Lyme disease after an Ixodes scapularis tick bite” (!!!)

The 2001 study was conducted in an area of New York with a high incidence of Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme) infection. Like the Israeli study, it was also a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, but unlike the Israeli study, they only gave patients a single dose of doxycycline. The results? One out of the 235 people treated with doxycycline got Erythema migrans, the bull’s-eye rash that indicates a Borrelia burgdorferi infection. In the placebo group (people who didn’t get antibiotics) 8 out of 235 developed the rash and tested positive for infection. Their conclusion: a single dose of doxycycline can prevent Lyme if given within 72 hours of the tick bite.

If these two studies are not convincing or current enough, the doctors from the Israeli Medical Corps published another study in 2010. First, they inform us that “Since 2004, the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) has mandated the prophylaxis of tick-bitten subjects with a five-day doxycycline course.” (That has me thinking the Israelis are pretty smart.) Just to make sure they were doing the right thing, in this study, they decided to analyze all the tick bite and TBRF cases in their records from 2004-2007.

Here’s what they say:

Of those screened, 128 (15.7%) had tick-bite and were intended for prophylaxis, of which four TBRF cases occurred-3.13% attack rate compared with an expected rate of 38.4% in these bitten individuals without prophylaxis (RR = 0.08, number needed to treat = 3). In all cases in which screening and prophylaxis were provided within 48 h of tick bite, complete prevention of TBRF was achieved. No cases of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (JHR) was recorded.

What does that mean? Only 4 of the 128 people who were treated with doxycycline developed TBRF, a rate of 3.13%. The expected attack rate was more than 10 times that, 38 percent, so without the doxycycline policy, it would likely have been 48 people with TBRF instead of 4. One more thing. There was a reason those four people got sick: they were given the doxycycline later than 48 hours after being bitten!

The Big Picture

How does this research affect you as a patient who has been bitten by a tick and contracted an infection or as a patient who could potentially be bitten by a tick in the future?

The research shows us that, if treated within 48 hours with 5 days of Doxycycline, most–if not all–cases of Borrelia infection and resulting symptoms can be prevented. If you could get an appointment with an infectious disease specialist who recognizes this fact within 48 hours of being bitten, you could probably avoid a lot of potential suffering. The problem is that to see a specialist, you usually need to be referred by your primary care doctor. Some of us can’t even get an appointment to see our primary care doctors within 48 hours, and some of the primary care doctors don’t even know how to spell Borrelia (no offense to primary care doctors who can spell it), let alone diagnose it with a simple blood test. And most of them certainly don’t know that the best thing to do would be to prophylax you with doxycycline.

Let’s put the numbers in perspective. In 2010, the CDC reported over 20,000 confirmed cases of Lyme (Borrelia burgdorferi) and an additional 10,000 probable cases. The CDC’s number of cases (which I believe, as with burgdorferi, are severely underreported) for 1990-2011 for Borrelia hermsii (TBRF) is 483. If 35% of those Borrelia cases had been prevented with prophylaxis, that would mean 10,669 fewer sick people.

So what can you do? Here’s a list of my suggestions:

- If you’ve been diagnosed with a tick-borne illness, make sure that every one of your doctors knows it, even the ones you don’t like and the ones you don’t go to very often. All doctors, not just infectious disease doctors, need to be aware of how prevalent these infections are.

- If you are bitten by a tick, insist that your primary care doctor prophylax you with doxycycline for five days. You can even print out these PubMed article abstracts and bring them to your appointment. Many doctors can be reasoned with, and if they won’t listen to you, sometimes they’ll listen to the New England Journal of Medicine.

- If you are bitten by a tick, try your best to save the little beast. You can store it in an old prescription bottle or a jar. (Labs like Quest Diagnostics also distribute collection containers to some doctors’ offices.) Inform your doctor that you are brining the tick to your appointment and you want to have it tested. Having ticks tested helps with more accurate CDC reporting about which areas have infected ticks.

- Getting the tick tested doesn’t mean that you don’t need to get tested. The tick testing takes longer than the people testing. On the off-chance that prophylaxis doesn’t work for you, you’ll need to get more treatment if you test positive.

- As always, the best way not to get a tick bite is not to be in areas where ticks live and not to be around animals that carry ticks. Follow tick-exposure prevention best practices. This includes keeping your home and yard free of mice and rats (on which the hermsii-carrying ticks feed) as well as deer (on which the burgdorferi-carying ticks feed).

That’s all for Tick-Lit Tuesday. Stay informed and stay well!

Eat Your Eggs, Benedict! 04/22/2012

Posted by thetickthatbitme in Choline Diet, Whole Person.Tags: Anaplasmosis, benedict, Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia hermsii, choline, diet, eggs, HBO, inflammation, Lyme, mushroom, recipe, salmon

5 comments

If you know my story, you know that when I was diagnosed with B. hermsii and Anaplasmosis, my doctor put me on a high-choline diet. Why choline, you ask? Choline is a B vitamin that aids in the transmission of nerve impulses from the brain through the central nervous system–this process is essential to functions like memory and muscle control. Since Borrelia like to attack the central nervous system, choline is especially important for people with (past and present) B. hermsii and B. burgdorferi infections. People who eat diets high in choline have also been shown to have lower levels of inflammation (like inflammation of the joints in Arthritis) than people who don’t. You can read more about choline here.

Enter the Benedict. It is by far my favorite egg-based dish, and I enjoy making it at home just as much as I do eating it for brunch in a fancy restaurant.

One large poached egg has 100 mg of choline, so if you eat two, you get about half of your recommended daily amount (425 mg for women, 550 mg for men). Add to that other high-choline foods like smoked salmon (129 mg), Canadian bacon (39 mg), portabella mushrooms (39 mg), spinach (35 mg), asparagus (23 mg), avocado (21 mg), and tomato (6 mg) to get your choline fix!

Here are my top five Benedicts:

1. Old Fashioned but Fried

for those mornings (or afternoons, or evenings!) when I’m feeling traditional, yet lazy

I learned this simple recipe from my mother, and it

brings back all kinds of fond childhood memories. A toasted whole-wheat English muffin, topped with pan-fried Canadian bacon and over-easy eggs (make sure they’re still a little runny, because that’s the best part). The hollandaise sauce I usually make with one of those sauce packets you can find in the grocery store (next to the gravy packets). It’s easy–you only need to add milk and butter–and, in my opinion, it tastes better than the from-scratch hollandaise recipes I’ve tried. Because of the butter and bacon, this is a slightly fattening meal, so I balance it with a side of boiled asparagus, which tastes delicious with the hollandaise sauce and adds 23 mg of choline to this meal!

Choline count: eggs 200 mg + Canadian bacon 39 mg + asparagus 23 mg = 262 mg of choline

2. Crab Benedict

for when I’m feeling crabby or rooting for the Terps

I’ve never made this one at home, but I’ve had it at Toasties Cafe, and it is delicious!

Choline count: eggs 200 mg

3. Portabello Mushroom Benedict

for the fungus-lovers amongus

If you’re looking for a meatless meal or just craving these yummy mushrooms, this is the Benedict for you. Check out Jackie Dodd’s recipe at TastyKitchen.com, which also includes spinach, tomatoes, and Sriracha for a kick!

Choline count: eggs 200 mg + portabello mushrooms 39 mg + spinach 35 mg = 274 mg of choline

4. Tomato Avocado Benedict

because I’m a California girl

My mouth was watering as I scrolled through SoupBelly.com’s deliciously illustrated recipe for this west-coast Benedict. If you want to make it even more California, use sourdough English muffins.

Choline count: eggs 200 mg + avocado 21 mg + tomato 6 mg = 227 mg of choline

5. Eggs Hemingway

for when I’m feeling literary

This one may seem a bit fishy, but I assure you it’s delicious and packed with choline. It’s also called Norwegian Benedict. Here’s a recipe at food.com that includes not only salmon but spinach, too!

Choline count: eggs 200 mg + smoked salmon 129 mg + spinach 35 mg = 364 mg of choline

Now that I’ve made myself really hungry, I’m going to go make my own Benedict. Hope you enjoy these eggcellent (sorry, I couldn’t resist) high-choline meals!

Curious about Tick-borne Infections? 04/21/2012

Posted by thetickthatbitme in TBI Facts.Tags: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia hermsii, diagnosis, facts, infection, Lyme, Lyme Disease, TBI, tick-borne, treatment, ugly stepsister

2 comments

Happy Saturday, loyal readers!

I thought I’d point out that I’ve added a new section to the blog: Infection Fact Sheets. One of my goals with this blog is to give you, my readers, access to as much factual information about tick-borne infectious diseases–or TBIDs, as I like to abbreviate them–as possible.

Since you’ve stumbled upon this blog, I’m sure you’ve heard of Lyme Disease, but do you know the name of the bacterium that causes it? Are you familiar with the common and not-so-common symptoms? What about the different drugs that are used to treat this infection? Check out the fact sheet here.

And let’s not forget Borrelia hermsii, which I consider to be like Lyme’s neglected ugly stepsister. Nope, no press for Ms. B. hermsii… Take pity on her (or if not her, me, a hermsii survivor) and pay a visit to her fact sheet.

If I were truly going to put my teacher hat on and plan a lesson for you, I’d tell you to make a K-W-L chart and take notes!

Once you’re done with the Borrelia sisters, you’ll probably be hungering (or worrying?) for more TBID info. Here’s a list of what’s to come: Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis (WA-1), Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsia (Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever), and more!